The Architecture of the Cloud

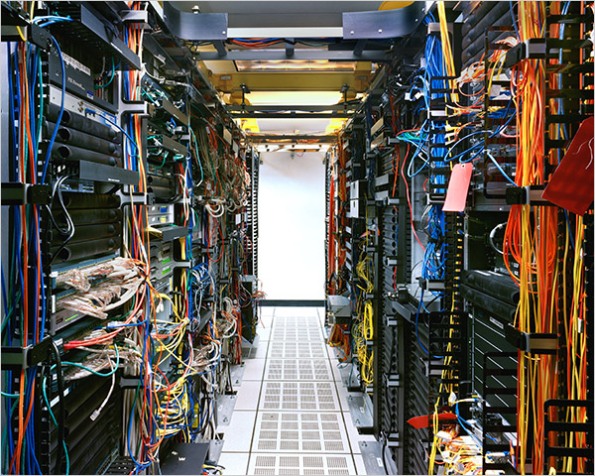

The NJ2 Data Center in Weehawken, NJ ('Data Center Overload' Tom Vanderbilt for the New York Times, 2009)

My interest in information technology and its architectural implications began after reading an article by Tom Vanderbilt entitled Datatecture in the New York Times magazine of June 2009. The article talks about massive concentrations of servers called ‘data centers’ that form the hidden infrastructure behind all of our activity on the internet.

Despite the fact that data centers are essentially warehouses full of machines with no human presence, their architectural significance is both intriguing and indisputable. Part of the appeal lies in the secrecy of data center locations and specifications. Rich Miller, founder and editor of the web site Data Center Knowledge, compares the security concerns to the movie ‘Fight Club:’ “The first rule of data centers is: Don’t talk about data centers.” The hesitation to divulge any information about these facilities seems justified given the importance of the data being stored on the servers (aside from the trivial tweet or Facebook status update, of course) and the increasing competition brewing between web juggernauts Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft.

The data center is also a building typology that has been virtually disregarded in the architecture world. While surely an effective security measure, the nondescript facade of the typical data center is devoid of any discernible architectural features. Artistic expression appears to be the last priority when designing a building that is essentially a machine.

Worldwide demand for data centers is currently rising, and the pace is expected to accelerate as more people obtain access to the internet and the web itself continues to grow. As Mr. Vanderbilt points out, “the number of servers in the United States nearly quintupled from 1997 to 2007,” and approximately 10,000 servers are added to the pool every month. Furthermore, since 1999, the African continent (and its one billion residents) has increasingly become connected to the internet through a complex network of undersea cables. Large web companies are also seeking to reduce the distance between their servers and their users–a condition known as latency–and consequently, the time it takes users to access information. Adding 150-500 milliseconds to the time it takes to access search results may seem inconsequential to most, but a 100-millisecond delay allegedly costs Amazon 1% in sales revenue. The best way to solve this problem, of course, is to build more data centers. The explosion of data centers combined with their striking environmental consequences, presents a potential opportunity for architectural innovation.

Globally, data centers consume an estimated 1-2% of the world’s electricity, and the standard Google search produces 0.2 grams of carbon dioxide. This doesn’t sound like much, but extrapolating these carbon emissions over a billion search queries per day adds up quickly. ‘Google Instant,’ a service that provides updated search results after every character is typed into the search bar, requires much more energy and yields greater carbon emissions. Stated another way, a Google Instant search for the word ‘architecture’ generates 12 separate search queries (one for each letter) and therefore produces 12 times the CO2 emissions of a standard search.

Despite the fact that a standard Google search is, according to EPA estimates, 4,500 times more energy efficient than a drive to the library, inefficiencies abound in the design of data centers. The primary consideration is providing chilled air to cool the servers. Designers are approaching the problem from multiple angles–allocating hot and cold aisles among the rows of server racks, employing computational fluid dynamics to improve server layouts, and even opening the walls of the building to expose the servers to the naturally-cold air of northern climates. Yahoo has even utilized the colder climate of Lockport, New York for one of its recent chicken coop-inspired data centers.

The most fascinating development, however, is the dissolution of big-box data centers into widely distributed, densely-packed server capsules. Michael Manos, former general manager of data center operations at Microsoft, envisions the future of the data center as a series of these pre-equipped server farms that can be plugged in to an infrastructural node providing power, water, and network connectivity wherever they are needed. One could imagine a fleet of mobile data pods reorganizing themselves on an urban scale to maximize network speed and data capacity…